Blur won no awards at the 82nd Venice Film Festival, which wrapped yesterday. This year’s competition featured thirty projects. There were three winners, but Blur dominated conversation on Lazzaretto Island where the Immersive Competition took place. From the moment I arrived the refrain was constant: “Did you see Blur?” Demand was far greater than supply. Because of the cruel math of throughput and utilization, over ten days, only three hundred people experienced Blur. Forty people a day.

Blur is unlike anything I have ever seen. It combines live performance and mixed reality in a way that is fresh, surprising, and profound. And yet I can’t tell you exactly what happened, or exactly what it means. Like a memory, its force comes in fragments.

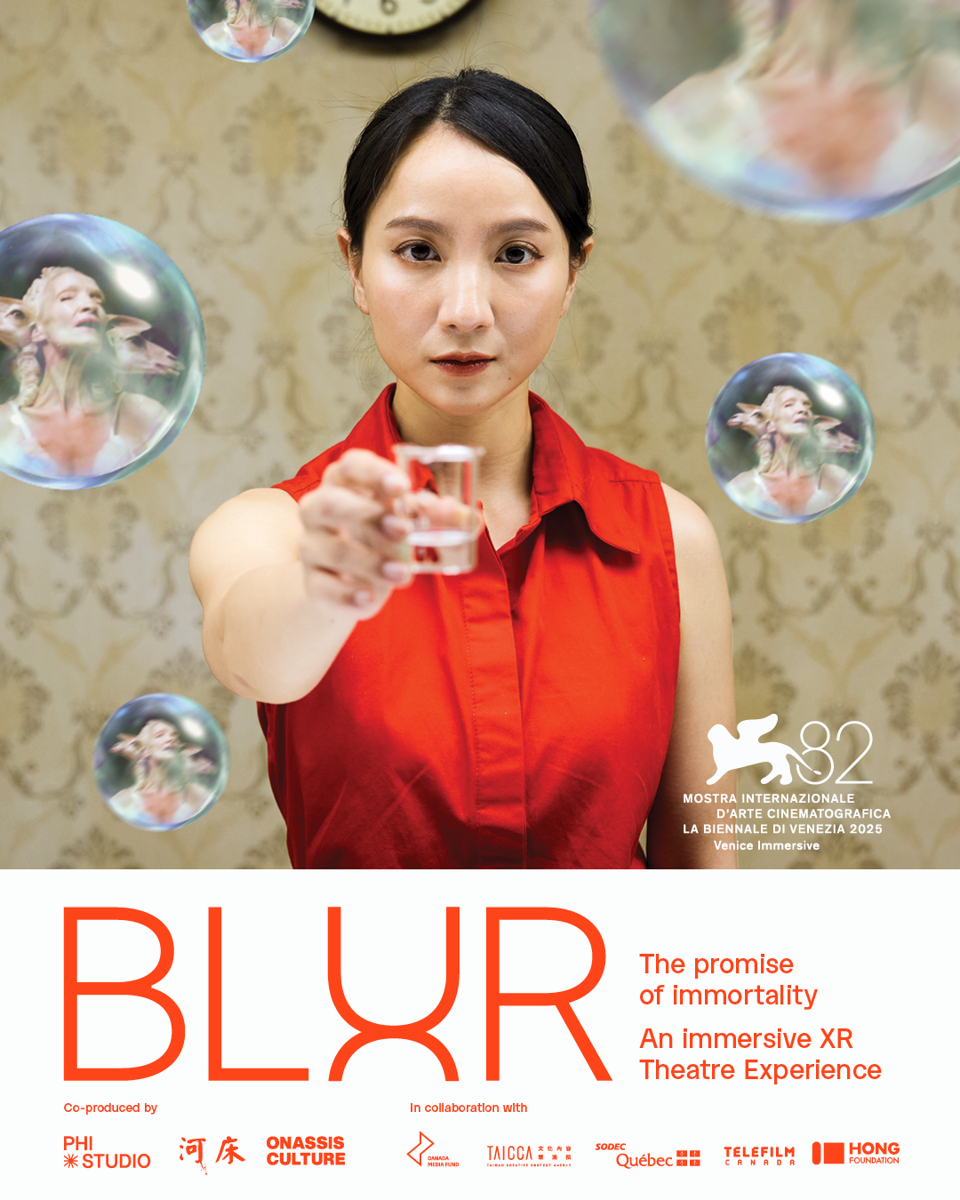

My journey began with a silent docent in a red dress who led me down a hallway. At the end was another Asian woman, also in a red dress. They could have been twins. She beckoned. When I approached, she reached out and gently took my hand. Without explanation she traced the number “11” on my palm. It was a startling gesture. In theater you don’t expect to be touched, least of all in VR where the headset usually creates distance. Instead, there was an intimacy that disarmed me. She then produced a small penlight and directed me to look into it. For a moment I thought of Men in Black, as though my memory were about to be erased.

Still image from ‘Blur.’

Venice Immersive

I was then taken into a narrow, darkened room with six chairs. On mine was a Meta Quest 3 headset, marked with the same number she had written on my hand. A flimsy bookshelf was built into a flat on one side. I put on the headset. Inside, I could see the others as translucent, ghostlike figures made of particles of light, each leaving glowing trails when they moved. The woman in the red dress reappeared, now as a very convincing avatar, not the same as my abstract one. The bookshelf opens to reveal a glowing path. We follow her through the wall.

That began a twenty- or thirty-minute free-roaming journey that unfolded across multiple levels. Physically we were walking in circles in a room of about four hundred square feet, but inside VR it felt like a corridor extending endlessly. The tech trick erased the boundaries of space, creating the sensation of a long and unpredictable passage.

Directed by Craig Quintero of Taipei’s Riverbed Theatre and Phoebe Greenberg of Montreal’s PHI Centre, ‘Blur’ combines live performance with free-roam VR.

CHENG-YU LI

The imagery was fragmented, dreamlike, sometimes cartoonish. I saw the woman with a young boy in a line-drawn sequence. A hospital scene emerged, heavy with the suggestion of loss. Later, a geyser erupted, spawning eyeballs that float upward in bubbles. The scenes were surreal and poetic. Like dreams they are constructed to be remembered imperfectly.

Then came the moment that stunned me the most. As I followed the path I confronted myself. My own double hovered before me. He smiled. It was uncanny and unforgettable, a simple effect that landed with force because of what it meant personally in that instant. And then it was over.

When I removed the headset, co-director Craig Quintero was waiting. He asked what I thought. All I could say was, “I’m not sure what just happened, but it was amazing.”

There is a veil of mourning over the whole piece.

Blur

That reaction was the point. “What if we could defeat death?” Quintero said in his director’s note. “As we seek to unwrite the laws of nature we simultaneously threaten to undermine our fundamental understanding of humanity. It seems fitting that, in Blur, we are using VR, AR, and AI to step into the unknown.”

Greenberg approached the project from a similar place. “Craig and I met at Venice Immersive and recognized an opportunity to explore the intersection of technology, storytelling and ethics,” she said. “The idea of bioengineering, cloning, and the ethics of DNA harvesting became the backdrop to a story of loss and tragedy.”

The Montreal-based PHI Centre, which Greenberg founded in 2012, has become a hub for new media art, bringing together cinema, music, theater, and XR. “Blur is a deeply emotional work that reflects PHI Studio’s mission to amplify bold, immersive storytelling,” she said in Venice. “We are incredibly proud to see it recognized here, where artistic risk and innovation are celebrated.”

Quintero, who has staged more than fifty surreal, image-based productions with Riverbed Theatre in Taipei, sees Blur as part of a continuum. “Since founding Riverbed in 1998 we’ve gone from staging performances for one person in a black box to productions in 1,500-seat theaters. Now, as we venture into XR, it has been remarkable to work with Phoebe and our collaborators as we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible.”

The project took over two years to produce. It premiered at the Taiwan National Theater before traveling to Venice. Along the way, it drew on a wide range of collaborators, from choreographers to visual artists. “To have traditional artists find a pathway into this digital world was super exciting,” Greenberg told me. “The role of an artist is not to give answers, but to ask questions.”

That philosophy explains Blur. It poses questions rather than delivering answers: Can science heal a broken heart, or will it unravel what makes us human? In its world, resurrected mammoths roam, AI governs underground facilities, and human-animal hybrids embody both triumph and ambiguity. Yet none of that lands as exposition. It comes as fragments, flashes, and encounters.

Venice Immersive was created for works like this. When the Biennale launched the program in 2017, it was the first major festival to place XR in competition. The symbolic weight of the Golden Lion matters, not just to the artists but to the entire field. Previous winners include Eliza McNitt’s Spheres and Laurie Anderson’s To the Moon. McNitt in fact was the Jury President, having won several years ago.

Blur is a theatrical experience with a beginning, middle, and end, but not a linear story. It is surreal, disjointed, and unforgettable. Like its title, it is a blur, moving from experience to memory and then lingering long after.