By the 25th anniversary of his company and the 2001 retrospective at the Guggenheim, which reportedly drew 29,000 visitors a week, Armani was still immensely successful and powerful, yet no longer le dernier cri. During the early years of the second millennium, he launched his hotel chain in partnership and assumed control of his manufacturing facilities to ensure vertical integration. Where he could not self-produce, he licensed, but only if he was ensured the last word (it was precisely this criterion that led to his exit from a highly profitable partnership with Luxottica).

He was, reputedly, approached several times with offers of investment from private equity groups and others keen to join the early boom of the conglomeration of luxury, but chose to keep the house he built his and his alone. He recounted once that three pitching investors had asked for a meeting with their banker. Armani said, “He was the most powerful man in Italian banking, and while the others spoke, he sat there, not saying a word. Then he looked over at the other men and said, ‘My dear sirs, Mr. Armani doesn’t need us. Let’s go.’ ”

Armani remained a dedicated advertiser in the fashion press (the fateful 1976 call from Barneys came after it saw his first campaign in L’Uomo Vogue), but increasingly his collections were truer to himself than the times. And such was the power of his name that he had transcended the limits of that press and even the fashion system in general. As Franca Sozzani, the late editor-in-chief of Italian Vogue, once noted: “Like all the truly great designers in fashion history, Giorgio Armani is about style, not fashion. They find their style, and they stick to it, and that’s what he has done.”

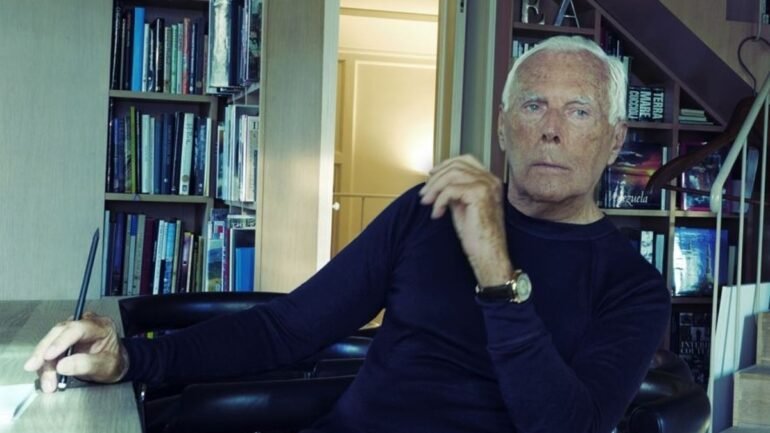

In manner, Armani was reputedly sometimes reserved or prickly. During the regular post-show press conferences for the Italian press, he would on occasion lob a rhetorical grenade in the direction of Prada or Dolce & Gabbana to the general merriment of all (Prada and Dolce & Gabbana apart). He often explained his bearing as shy. Despite that, the Armani aspect was formidable and his personal aesthetic ascetic. He was dedicated to personal fitness.

Part of the designer’s apparent severity, and most certainly his seriousness and overall sobriety (although he confessed to taking LSD once and getting drunk a single time in his life), was likely the result of a childhood spent in straitened circumstances. He was raised in the town of Piacenza, close to Milan, in the 1930s and 1940s. His mother Mariù — after whom his beloved yacht was named — was a formidable matriarch charged with protecting Armani, his sister Rosanna and brother Sergio, through Allied bombing raids. Their father, Ugo, an accountant of Armenian lineage, found work hard to come by after the war. One of young Giorgio’s friends was killed by an explosion — a landmine, or gunpowder — on a Piacenza bomb site that left him badly scarred and in need of a 40-day hospital stay. This inspired him to pursue an initial ambition to be a doctor before he did military service and eventually found himself in Milan, the city that would make him and to which he would contribute so much.

Armani worked to the last, and even in his final collections would check every single look before ushering his models out onto the runway of the theatre created for him by the esteemed Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

His mantra, he once observed, was that “perfectionism, and the need to always have new goals and achieve them, is a state of mind that brings profound meaning to life.”

The company statement said funeral arrangements have been set at the Teatro Armani in Milan from Saturday, 6 September to Sunday, 7 September, and will be open from 9 am to 6 pm.

Comments, questions or feedback? Email us at feedback@voguebusiness.com.