Every April and May, the MA Chidambaram Stadium in Chennai, India, fills with devotees of the Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket team Chennai Super Kings, all wearing their trademark banana yellow. And every time one man—Mahendra Singh Dhoni, the team’s captain and a grizzled, canny veteran—jogs out to bat, arms stretching and flexing, bat held like a cudgel, the crowd seems to melt into one hoarse, fevered, perspiring organism. When he steps out, the spectators cheer like delirious banshees, the howl of paper-cone trumpets sounds around the stadium, and a percussive banger from some recent Tamil film or another drops on the loudspeakers. It’s astonishing that Dhoni can even hear himself think.

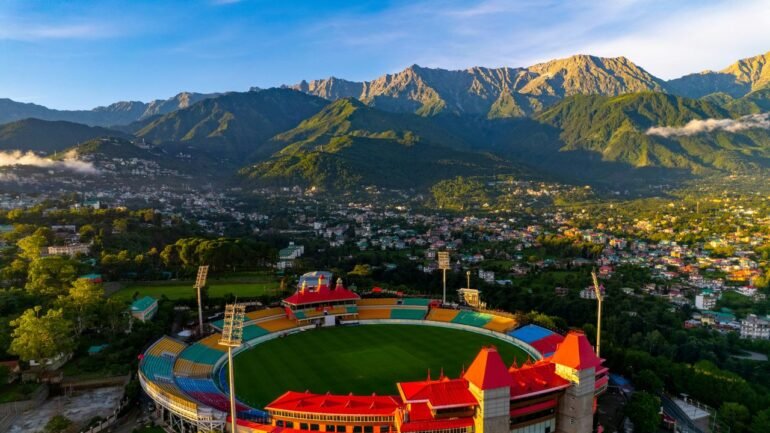

The IPL is not our grandfather’s cricket, or even our father’s. The older version of the game, called Test cricket, spreads over five full days of play, and its duration as well as its colonial-era quirks (players wear white while representing their country and take breaks during the day for lunch and tea) have often lent themselves to ridicule. I won’t lie: That is the form I best prefer, not only for its novelistic twists and turns but also for the languid experience of spending a whole day, or five, in a stadium, to watch a plot unfold and its characters respond. Test cricket still exists and in fact is more exciting now than it has been for a long time: fewer draws, more powerful, hectic cricket, and tight results. The venues can be varied and exhilarating: English grounds with turf as immaculate as a billiards table; the stadium in Dharamshala, in northern India, cupped in the lap of the Himalayas; the stadium in Galle, in southern Sri Lanka, cheek by jowl with an old Portuguese fort and the waves of the Indian Ocean.

But to know fandom and spectacle at their most frenzied, look at the IPL. As sports tourism becomes a more powerful engine for travel, offering an unexpected gateway into a society and its culture, travelers can get to know India through this brisk, energetic version of our most-beloved game. Watching the Chennai Super Kings at the MA Chidambaram Stadium is an exhilarating complement to the city’s more sedate rhythms—its long, palm-fringed beaches, its ancient temples, and its buzzing culture of music and dance.

The IPL began in 2008, not that long ago, compared with the almost century and a half that Test cricket has been around. But like a black hole, it has pulled everything into it: the biggest international stars, the money of investors and advertisers, and the appetites of India’s cricket fans, all 1 billion or so of them. In the IPL, franchises represent cities—just like the English Premier League or the NBA—and they play round after round of short, high-intensity games that culminate in a final. Each match, played under floodlights at night, lasts three and a half hours. There’s one brief inning for each team, which its batters spend trying to pummel the ball clean out of the park time and time again. Such a hit earns you six runs, and the team that ends up with the most runs at the end of the game wins.